The Independence of Brazil, one of the most significant chapters in the country’s history, was a multifaceted process that involved a variety of characters, events, and circumstances. While many iconic names, like Dom Pedro I and José Bonifácio, played a crucial role in this endeavor, the contribution of women in the fight for independence often goes unnoticed.

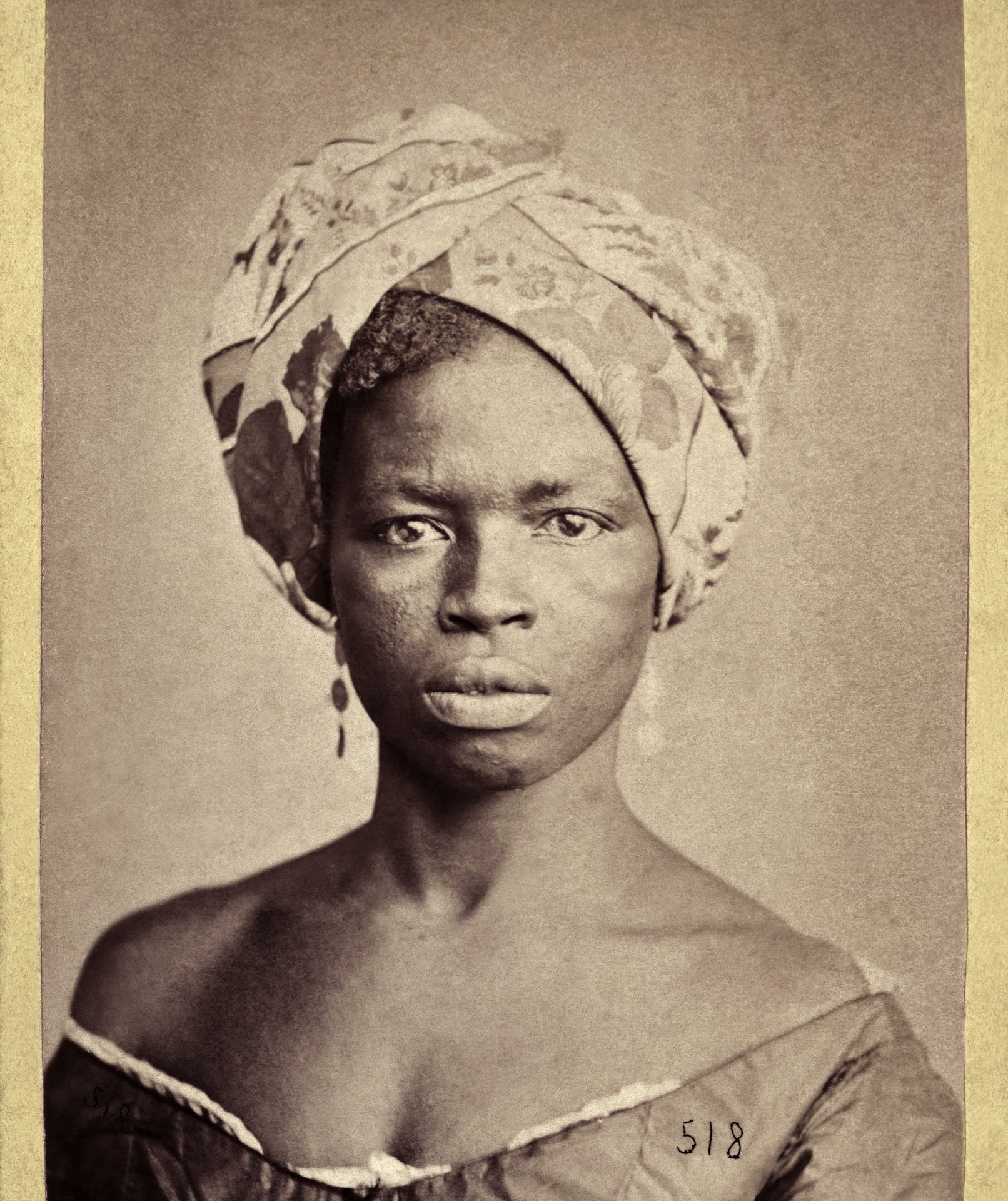

Among the various Bahians who fought for the independence of Brazil was Maria Quitéria de Jesus Medeiros (1792-1853). Orphaned of her mother at the age of 9 and raised by her father, she learned to ride, shoot, and hunt. On September 6, 1822, the provisional government of Bahia was established in the region where her father owned a farm. Soldiers were sent to the farms to explain what was happening and request assistance from men and ammunition to confront the Portuguese.

Maria Quitéria, enthused by the cause, wanted to enlist but was prevented by her father. She then sought help from her sister, who cut her hair and lent her her husband’s clothes. Thus, with short hair and dressed as a man, she presented herself in the village of Cachoeira as “Soldado Medeiros.” Quitéria joined the Artillery Regiment, but, as she was petite for handling artillery and cannons, she was transferred to the infantry.

Her escape from the farm occurred while her father was absent, and as soon as he returned, he began to search for her but found her already in the army. Despite the revelation that the “Soldado Medeiros” was not “he” but “she,” Maria Quitéria’s father could not get his daughter expelled from the force because she was useful. In addition to her willingness to fight, she had experience with weapons and was already receiving military training.

Her baptism of fire took place in February 1823, in Itapuã. She was mentioned in the order of the day for her bravery in attacking an enemy trench and taking several prisoners. In April, while advancing with water up to her chest, she prevented the landing of enemy troops at the entrance to the Paraguaçu River. She was received with great joy in Salvador along with the army that liberated the city from the Portuguese on July 2, 1823.

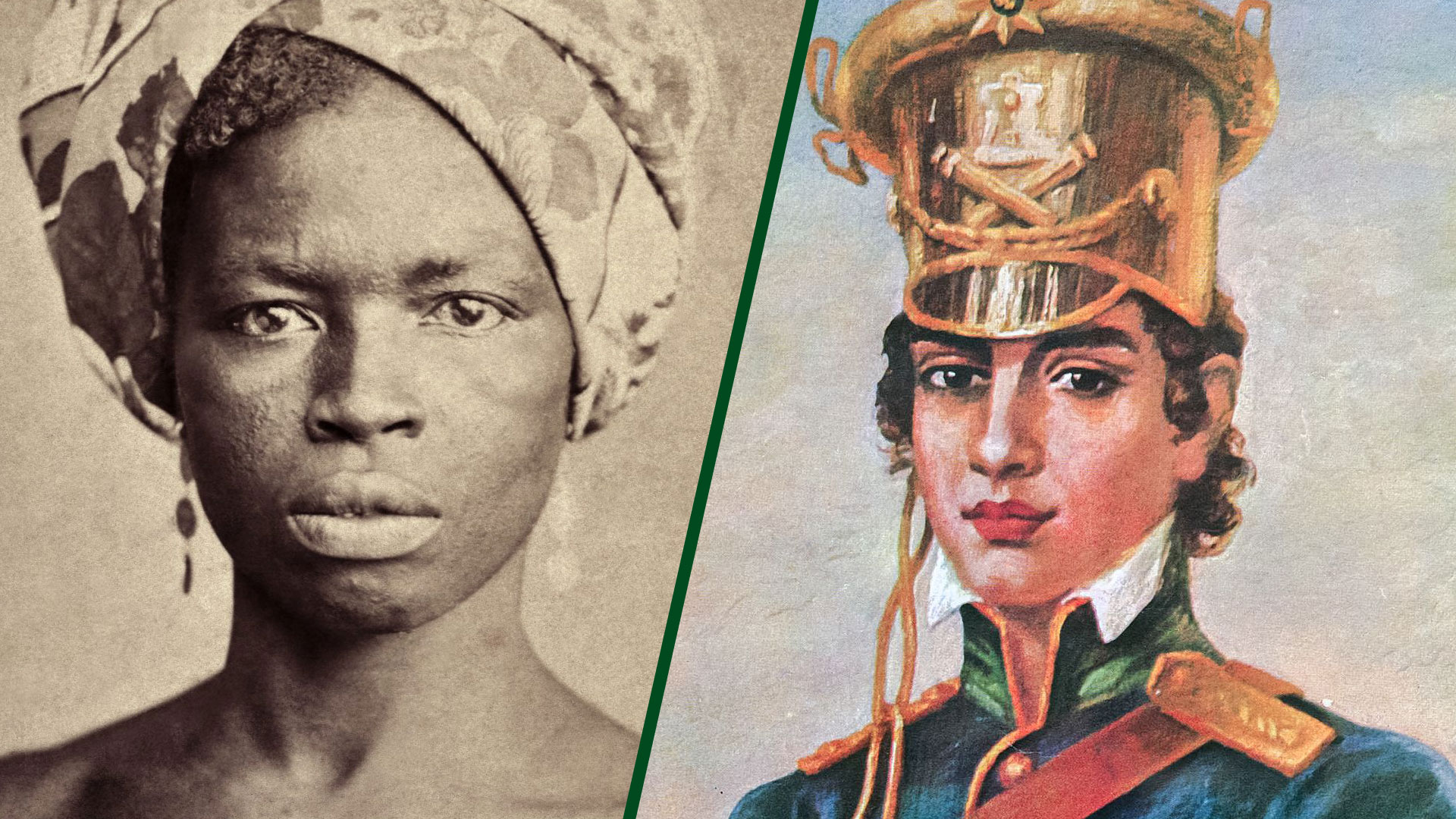

Another woman who is said to have stood out in the Independence of Brazil, according to popular tradition, was Maria Felipa, a resident of the island of Itaparica. She was described as a Black woman, a community leader, poor, illiterate, and a capoeira fighter.

Together with other women from the island, Maria Felipa decided to join the fight against the Portuguese. Initially, she acted as a spy, providing Brazilians with information about the movement of Portuguese ships and their positions. Later, she and her companions took action. They were said to have even seduced Portuguese soldiers, and when these soldiers undressed and were left vulnerable, they were beaten with “cansanção,” a plant that burns and blisters the skin. Once their enemies were neutralized, the women set fire to their boats.

Maria Felipa and about forty other women, in addition to using seduction, also engaged in armed combat with machetes and any other items they could find. They were said to be responsible for setting fire to the warship “Dez de Fevereiro” on October 1, 1822, at Manguinhos Beach, and to the ship “Constituição” on October 12, at Convent Beach. Maria Felipa lived in Itaparica until her death in 1873.

Dona Leopoldina had evidence of the loyalty of the women of Bahia. On August 23, 1822, she received a group of ladies in Rio de Janeiro who brought her a manifesto signed on May 13 by 186 Bahian women. The document stated:

“The undersigned Bahian women, aware of the substantial contributions made by H.R.H. Prince Regent Dom Pedro to the politics and prosperity of all Brazil under the auspices of the constitutional principles that have been sworn to throughout the land, and fully committed to ending the anarchic system of disunity that could have torn this kingdom into as many independent states as its provinces, should the decree of the first of October of the past year be executed (…): And recognizing that in this heroic resolution, Your Royal Highness fully agreed with the decisions of your august and beloved spouse (…) thus showing how worthy she is of the throne to which the omnipotent will of empires has called her; filled with the utmost respect, after congratulating our compatriots for having such precious and august individuals among us, we offer our hearts, the only offerings nature has placed within the reach of our sex, so that posterity may have the due appreciation of Brazilian women, and Bahian women in particular.”

The letter was a recognition of Leopoldina for her involvement in the Day of Fico. The future empress used the manifesto to, in the postscript of a letter, subtly prod the still undecided Prince Regent, Pedro, saying that this was “proof that women have more spirit and are more devoted to the righteous cause.”

By exploring the stories of these remarkable women, we can gain a more comprehensive and rich understanding of this crucial moment in the history of Brazil and the struggle for independence.

Reference: REZZUTTI, Paulo. Independência: a história não contada: A construção do Brasil: 1500-1825. Brazil: Leya, 2022.

Matheus Araújo

Matheus is an entrepreneur at Araujo Media, where he serves as CEO and Creative Director. He shares analyses on his personal blog "matheusaraujo.me" and is currently pursuing a degree in Advertising and Propaganda. Moreover, he has a passion for history, particularly that of Brazil, which led him to become the founder and editor of the Brazilian History portal.