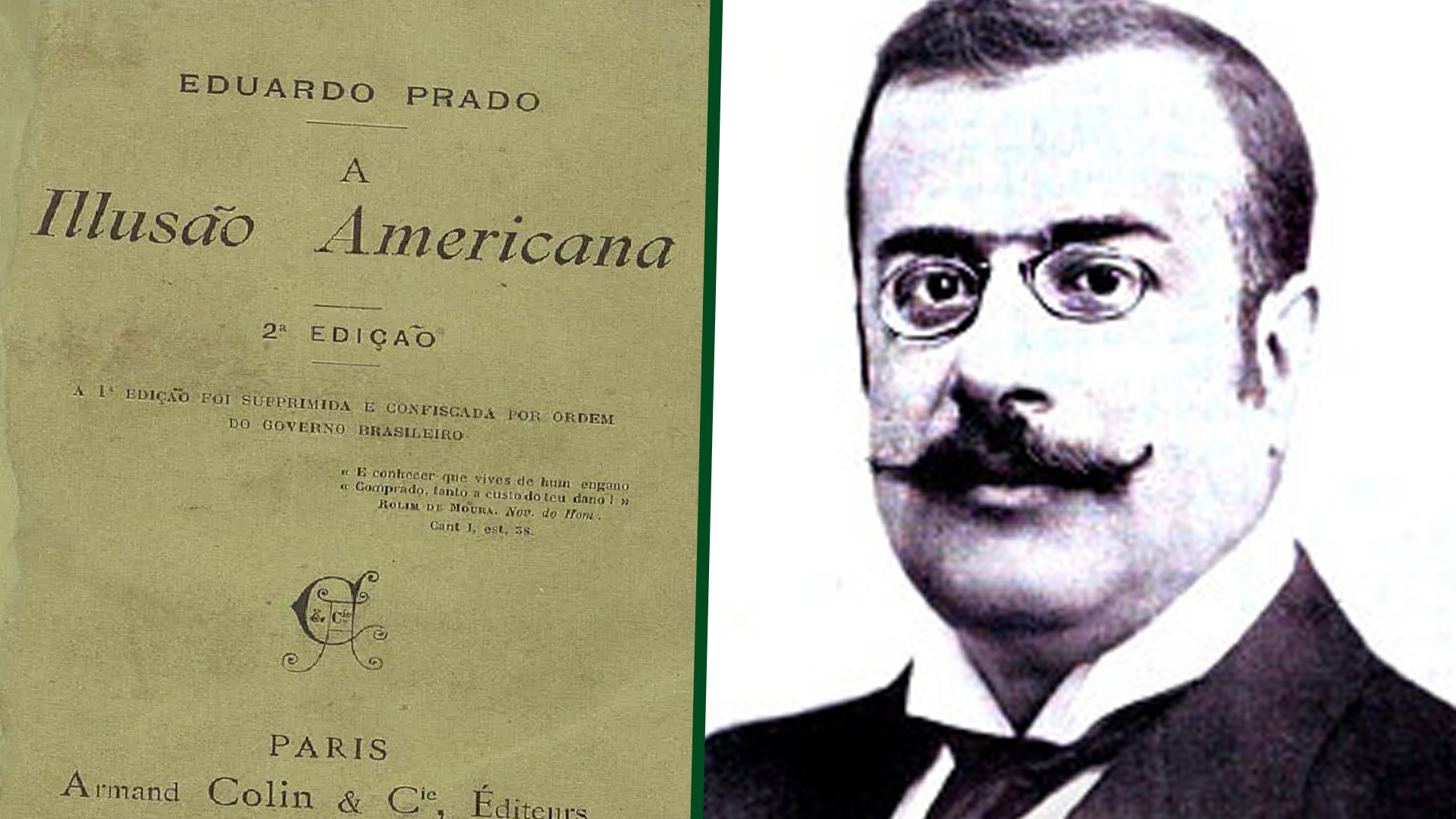

Eduardo Paulo da Silva Prado (São Paulo, 1860 – São Paulo, 1901), better known as Eduardo Prado, was one of the most notable Brazilian writers and political analysts. He was a founding member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters, a contributor to the work “Le Brésil” – published in 1889 on the occasion of the International Exhibition of Paris – and a friend of Barão do Rio Branco and the Portuguese writer Eça de Queirós.

As a staunch monarchist, Prado opposed the Republic openly since the 1889 Coup. His book “Events of the Military Dictatorship in Brazil” (1890) gathers the articles he wrote in Portugal against the new regime. As literary critic José Guilherme Merquior stated: “Eduardo didn’t fully grasp the sociological meaning of the Republic, but he astutely analyzed the motivations behind military republicanism: the social decline of the Army and the legalistic education of the officers, which prompted them to intervene in the political scene.”

One of the aspects he fiercely opposed in the Republic was the sycophancy displayed by many of its leaders towards the United States. He was highly critical of the spirit of imitation and idolatry cultivated by many republicans towards that country. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he foresaw the imperialistic spirit of the USA, which would manifest even more frequently in the centuries to come.

The book “The American Illusion” (1893), whose first edition was confiscated by order of the Brazilian government, is Prado’s most well-known and influential work. Its main objective was to demonstrate the incompatibility of essence and interests between Brazil and the USA. In a context where the nascent Brazilian republic sought legitimacy by emulating that country and seeking partnership and friendship with it, Prado was categorical in affirming that “the American brotherhood is a lie” and that “the American friendship (a one-sided friendship that, by the way, we alone preach) is null when it is not self-interested”.

According to him, the geographic contiguity of Brazil and the USA, both belonging to the same continent, would be simply a natural accident from which no other affinities should be drawn. Brazil would be separated from the USA “not only by a great distance but also by race, religion, character, language, history, and the traditions of our people.”

The author then compiles the aggressions and deceptions committed until then by the USA against Latin American countries, with a focus on Brazil. The intrinsic motivation would be “the deep contempt that the United States governments have for the sovereignty, dignity, and rights of the Latin nations of America.” The foreign policy of this country would be “selfish, arrogant, and sometimes submissive, depending on the interests of the occasion. And in any case, it is never guided by sentimentalism about forms of government.” Some political leaders of the USA would even propose, to the applause of many of their compatriots, the violent annexation of the entire American continent to the political center of Washington, expressly comparing Latin America to a ham to be devoured by Uncle Sam.

The juxtaposition of harsh realism, devoid of any ethical correction, with a feeling of superiority over Latin peoples, would have resulted in a constant disposition of the USA to crush weaker countries, regardless of whether they were more or less obedient to the commands and precepts emanating from that country. As Prado summarizes, “there is no Latin American nation that has not suffered from its relations with the United States.”

He then dissects the war waged by the USA against Mexico, subtracting about half of its territory from the latter, as well as analyzes the economic and financial subjugation of Mexico to the USA in the second half of the 19th century, despite Mexico having adopted the political institutions of the USA. He also mentions occasions when the USA violated the principle they themselves formulated in the Monroe Doctrine (1823) of defending American nations against European interventions, as, among other examples, when they recognized the usurpation of the Falkland Islands by England in 1831, supported the British invasion of the Honduran Islands and nearby territories of Belize, and abstained from defending Colombia and Ecuador from threats by the Italian fleet in 1888.

Regarding Brazil specifically, Prado refers, for example, to the USA’s indifference to Brazil’s attempts at independence and the delay in recognizing it, the American covetousness for the Amazon, the recurring piracy practices of Southern states against Brazil, the breach of commercial agreements made with our country, the USA’s refusal to defend Brazil in the Pirara Question when British emissaries occupied that Amazonian region, the USA’s support for Solano López in the War of Paraguay, and the outrage committed by the American minister Washburn who, in his book about the history of Paraguay, slanders and ridicules the Brazilian military forces and particularly vilifies the figure of Caxias, a Brazilian statesman and national hero.

According to Prado, the USA would also exert a negative cultural influence on Latin American countries. The pro-slavery inclination, which led half the country to take up arms against its own national unity, and the predatory capitalism, driven by an unrestrained pursuit of economic accumulation and ruthless exploitation of workers, would have shaped in the Anglo-Saxon republic a national character that is violent, racist, segregationist, fanatically materialistic, and devoid of respect for human life. The material abundance of that country would have its counterpart in a spiritual barbarism that, in other places, could only lead to degradation of customs and the decline of the nation. Prado feared that the Americanist inspiration of the newly formed Brazilian republic, by copying American political institutions, would also import its characteristic values and damage the typically Brazilian nature of seeking to soften contrasts, resolve conflicts through legal means, and value life and human beings.

It is true, however, that Eduardo Prado’s aversion to the USA was motivated less by strict nationalism than by resentment at the decline of political and ideological influence of European monarchies in Brazil, which he adored. Regarding Great Britain specifically, he saw its values and international actions as beneficial and humanitarian, despite the blatantly imperialistic nature they displayed, with plenty of tragic examples in China, India, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America itself, kept underdeveloped through commercial and financial submission. One could say, then, that Prado’s political intention was to preserve Brazil’s attachment to the British orbit.

Reference: PRADO, Eduardo. A Ilusão Americana. Brazil: Ed. Senado Federal, 2010.

Felipe Maruf Quintas. INTÉRPRETES DO BRASIL – EDUARDO PRADO E A ILUSÃO AMERICANA. Brazil, Octo 06, 2020. Website: Bonifácio. Available in: INTÉRPRETES DO BRASIL – EDUARDO PRADO E A ILUSÃO AMERICANA – Bonifácio (bonifacio.net.br). Accessed on: July 20, 2023.

Matheus Araújo

Matheus Araújo is the founder and editor of Brazilian History. Born in Rio de Janeiro and holding a degree in Advertising and Marketing, his passion for history led him to enroll at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, where he is currently pursuing a degree in History Education.