Throughout history, cities have undergone transformational changes, shedding old practices and embracing new ones. The city of Rio de Janeiro, with its rich tapestry of memories, is no exception to this phenomenon. Within its boundaries lie numerous examples of places and practices that have faded into the past, and among these, the Matadouro da Cidade (City Slaughterhouse) stands out as a poignant reminder of bygone eras.

The first incarnation of the Matadouro da Cidade was situated along the now-extinct shores of Santa Luzia beach. Established in 1774 under the decree of the Marquês de Lavradio, the vice-king, this public slaughterhouse played a vital role in distributing meat to the entire Rio de Janeiro region. “It was installed in 1774 by order of the vice-king Marquês de Lavradio in Santa Luzia, close to where the obelisk on Av. Rio Branco stands today. This type of work had to be conducted in isolated areas due to the mess it generated,” as highlighted by researcher Carlos H on the website Curiosidades Cariocas.

With the arrival of the Royal Family in Brazil in 1808, the Santa Luzia beachfront underwent a transformation. Dom João, a devout patron of the Santa Luzia church, utilized this route for his journeys. The renovations gave rise to residences along the shoreline, leading to the relocation of the Matadouro. The prospect of living in proximity to the blood and remains of animals was unappealing to the populace.

In 1838, the Matadouro da Cidade was moved to its new home in what is now the Praça da Bandeira region, then known as the Praça do Matadouro. As the Praça da Bandeira area evolved, the necessity of keeping the slaughterhouse at a distance from populated areas prompted yet another relocation. Santa Cruz, located in the still-isolated Western Zone, was chosen as the new site. “The installation, or rather, the transfer of the slaughterhouse to Santa Cruz was essentially a way of moving the ‘filth’ far away, where it wouldn’t cause inconvenience,” emphasizes a passage from the website Fatos, Fotos e Registros, overseen by Professor Deonísio da Silva.

Despite the challenges, the presence of the Matadouro Carioca spurred the development of worker settlements in Santa Cruz and made it the first neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro to have electric lighting, powered by the slaughterhouse’s generator. “In 1884, the D. Pedro II Railway (later known as Central do Brasil from 1899) established the Matadouro branch, with tracks encircling the building, a mere 700 meters from Santa Cruz Station. This branch operated until the 1980s when it was decommissioned,” reports Carlos H.

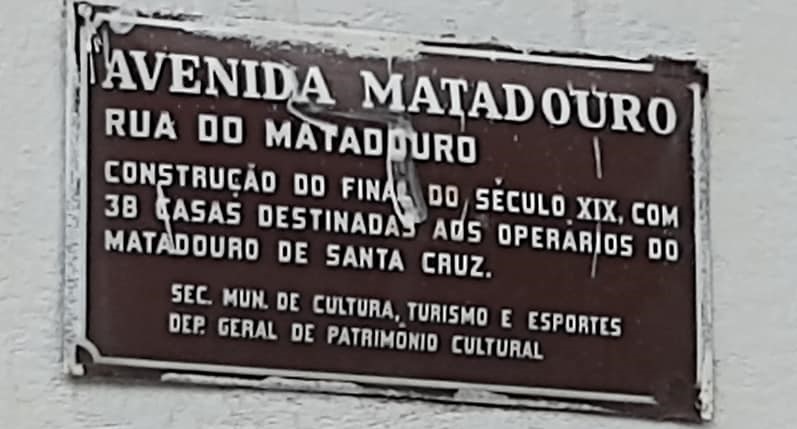

The Matadouro da Cidade itself was eventually shuttered. Today, the site is home to a technical school, the NOPH – Núcleo de Orientação e Pesquisa História de Santa Cruz (Center for Guidance and Historical Research of Santa Cruz) and the ECOMUSEUM. The area also boasts Avenida Matadouro, located on the Imperial Farm of Santa Cruz. Originally designed by landscape architect Auguste Marie Glaziou, the avenue now comprises only a short stretch, housing remnants of the old Vila Operária do Matadouro Industrial (Worker’s Village of the Industrial Slaughterhouse).

As a landscape architect, Glaziou was responsible for a multitude of projects in the Court, including the renovations of Passeio Público, the gardens of Quinta da Boa Vista, and Campo de Santana.

The Third Headquarters of the Matadouro Industrial, also known as the Imperial Slaughterhouse, was inaugurated on December 30, 1881, by Emperor Dom Pedro II, with the presence of Princess Isabel. To secure a workforce for the slaughterhouse’s operations, two rows of houses were constructed at the periphery of the administrative headquarters within the slaughterhouse compound. Locals dubbed this arrangement the “correr de casas” (line of houses) (Benedicto Freitas, 1950).

The Worker’s Village comprised four blocks (two of which remain), totaling 38 houses distributed as follows: 30 were divided into two units to accommodate more employee families, eight were unoccupied and reserved (one for supervisors, two requisitioned by the Slaughterhouse Administration, one for the literacy school for workers’ children, three for commercial purposes, one for the cattle agent, and one for leather workers).

“These houses were called Avenida Matadouro, serving as a form of assistance, a housing subsidy for the workers. Freitas documented 214 individuals, deemed of ‘absolute genealogical interest'” (Morais, 2019). Among the residents, there were 164 Brazilians, 38 Portuguese, 2 Spaniards, 7 Paraguayans, and 3 Africans, including 53 children (Freitas, 1950).

In essence, the transformation of the Matadouro da Cidade reflects not only the shifting urban landscape of Rio de Janeiro but also the intricate interplay between historical developments, social needs, and urban planning. From its early days on the shores of Santa Luzia beach to its final incarnation in Santa Cruz, the journey of the Matadouro mirrors the evolution of a city constantly adapting to its changing identity and priorities. As Rio de Janeiro continues to progress, its ability to embrace and preserve these layers of history contributes to the tapestry of its vibrant and multifaceted culture.

Reference: Diário do Rio. História do Matadouro da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Brazil, March 14, 2022. Available in: História do Matadouro da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro – Diário do Rio de Janeiro (diariodorio.com). Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

O Rio. Palacete Princesa Isabel – Antigo Matadouro de Santa Cruz. Brazil, [s.d.]. Available in: SEDREPAHC – Palacete Princesa Isabel – Antigo matadouro de Santa Cruz (rio.rj.gov.br). Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

Descubra Santa Cruz RJ. Avenida Matadouro: o Correr de Casas. Brazil, [s.d.]. Available in: Avenida Matadouro: o Correr de Casas – Descubra Santa Cruz RJ. Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

Barbara da Silva

Barbara has a History and teaching degree from UFRRJ and is currently pursuing a second degree in English Language Teaching. Passionate about heritage, culture, and social history topics, she manages the Mare Nostrum - Antiquity and Middle Ages page, collaborates with the Brazilian History portal, and conducts research on the Estado Novo (New State) period.