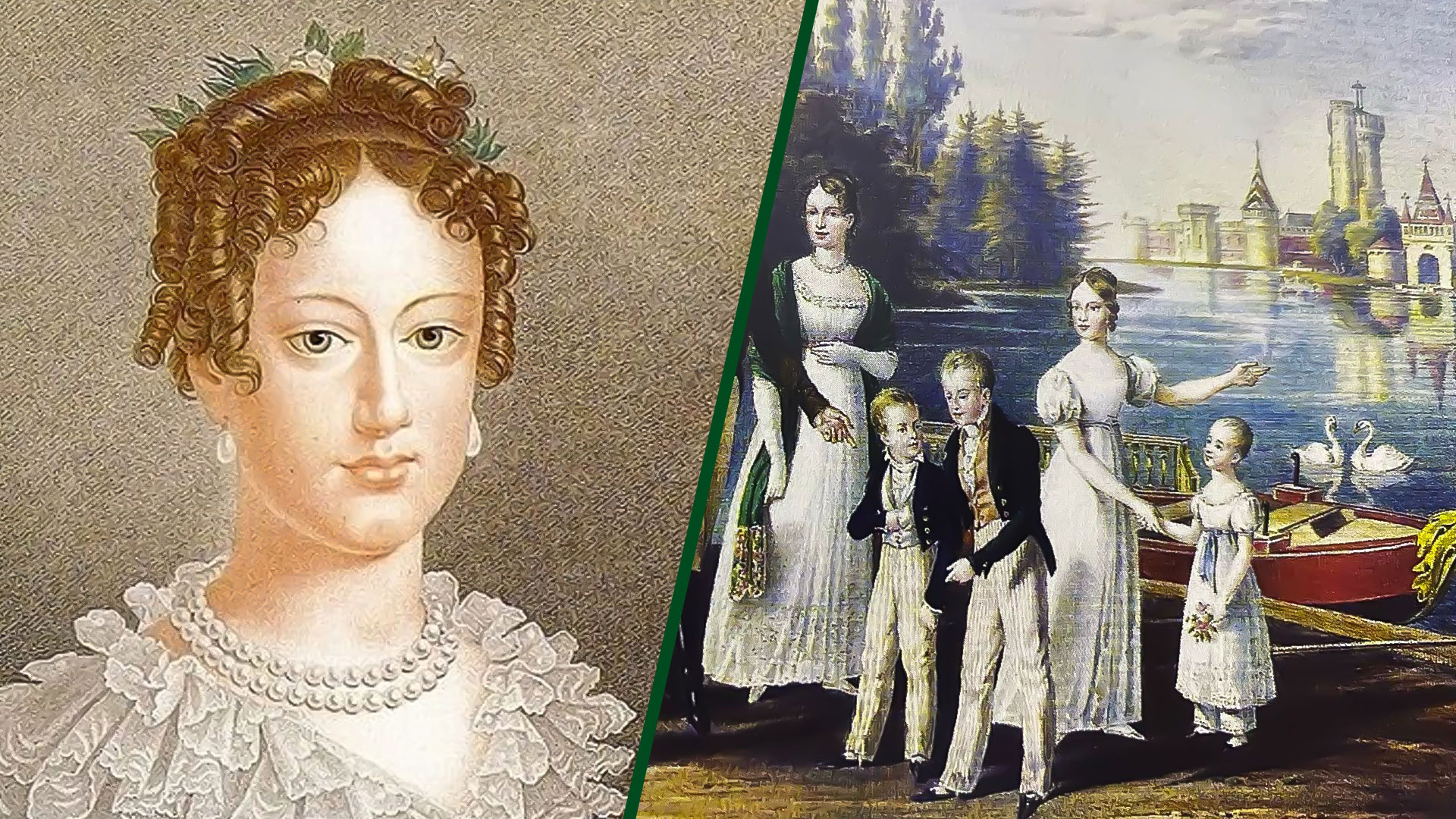

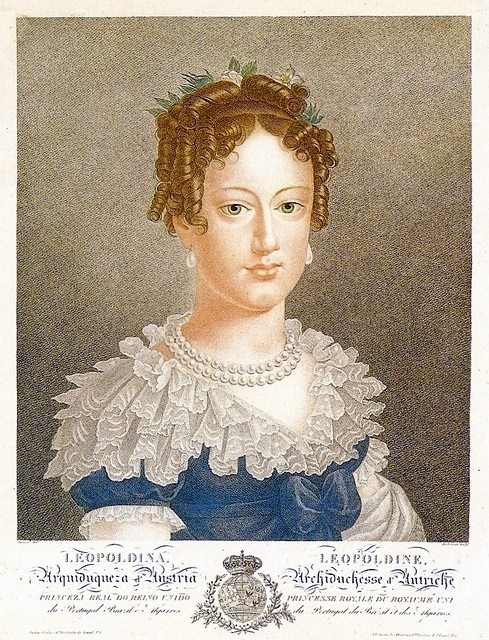

Maria Leopoldina werd geboren in 1797 in een van de meest conservatieve koningshuizen van Europa. Haar opvoeding was niet alleen gericht op persoonlijke ontwikkeling, maar ook op politieke plichtsbesef.

De strenge cultuur en opvoeding van een Oostenrijkse aartshertogin behoorden tot de belangrijkste criteria voor een prins om er een aan zijn zijde te hebben. Leopold II, de grootvader van aartshertogin Leopoldina, stelde de richtlijnen vast voor de opvoeding van de Habsburgse vorsten. Hij geloofde dat kinderen al op jonge leeftijd geïnspireerd moesten worden om hoge kwaliteiten te ontwikkelen, zoals menselijkheid, mededogen en de wens om het volk gelukkig te maken.

Het curriculum van de aartshertogen omvatte vakken zoals lezen, schrijven, Duits, Frans, Italiaans, dansen, tekenen, schilderen, geschiedenis, aardrijkskunde en muziek. In de meer gevorderde module werd wiskunde onderwezen – inclusief rekenen en meetkunde. Daarnaast omvatte deze gevorderde fase literatuur, natuurkunde, Latijn, zang en handvaardigheid.

Leopoldina's dagelijkse routine was als volgt: ze werd rond zeven uur wakker en ging om acht uur naar de kerk. Meestal studeerde ze van negen tot tien uur een bepaald vak met haar leraar, gevolgd door een andere les van elf tot twaalf uur in een ander vak. Ze rustte van twaalf uur 's middags tot drie uur, waarna ze haar studie hervatte tot acht uur 's avonds. Natuurlijk wisselden de vakken gedurende de week af, en ze volgde dit schema meestal van maandag tot en met zaterdag.

Al op jonge leeftijd toonde Leopoldina grote toewijding en waardering voor de natuurwetenschappen, met name mineralogie. De aartshertogin erfde de gewoonte om te verzamelen van haar vader: ze onderhield een verzameling munten, planten, bloemen, mineralen en schelpen. Tijdens een bezoek aan de Universiteit van Praag ontdekte de aartshertogin een bibliotheekgedeelte gewijd aan mineralogie. Leopoldina schreef in haar dagboek over dit bezoek en zei dat ze er uren kon doorbrengen als het haar werd toegestaan, en dat haar verblijf in de stad haar mineralencollectie aanzienlijk had uitgebreid.

Nu een ongewone weetjes: tijdens ditzelfde bezoek werd Leopoldina beroofd. Inderdaad – de aartshertogin, die vrijelijk door de stad zwierf zonder escorte, werd beroofd van haar rijtuig door een Praagse inwoner. Ze schreef in haar dagboek dat ze in een wankele hut op redding wachtte en dat haar voeten volledig doorweekt waren.

Een andere gewoonte die de Habsburgers aannamen, was deelnemen aan toneelstukken, opera's en balletten. Naast vermaak diende dit als een vroege training voor spreken in het openbaar. Door deze ervaringen raakten de kinderen hun verlegenheid voor een publiek kwijt en oefenden ze hun spraak- en stemprojectievaardigheden, vaardigheden die essentieel waren voor publieke figuren.

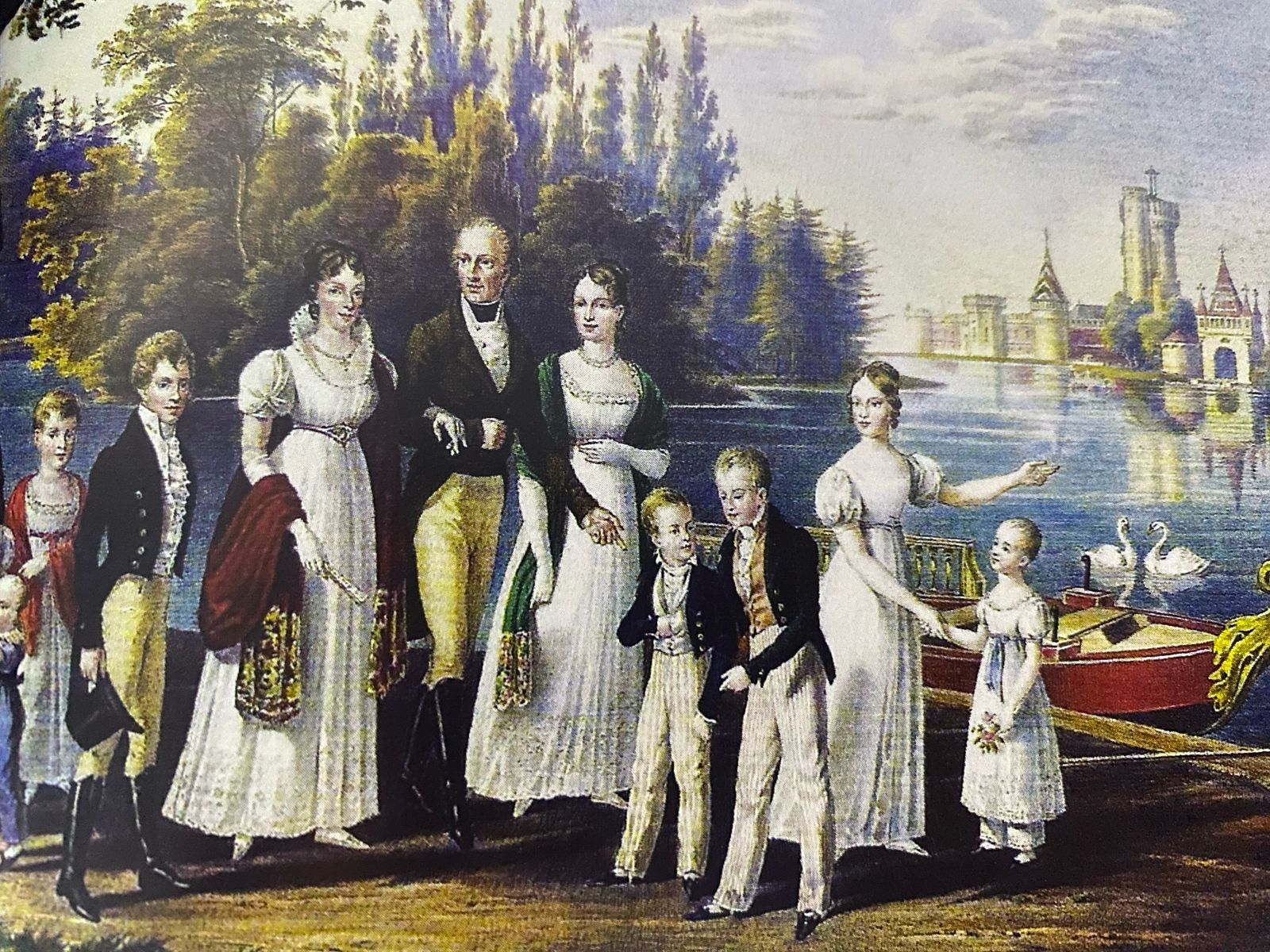

Leopoldina's dagelijkse leven was minutieus gepland, inclusief lessen, gebeden, brieven schrijven en familiebezoeken. De familie hechtte veel waarde aan het bewerken van het land en de landbouw. Niet toevallig, zowel in hun zomerresidentie in Laxenburg als in Paleis SchönbrunnEr waren tuinen waar de prinsen tot wel vierhonderd plantensoorten konden kweken. Het was heel gebruikelijk om Leopoldina en haar familie op het terras van het paleis bloemen te zien verplanten en stekken te nemen, zelfs van bloemen die door familieleden waren opgestuurd.

Elke aartshertog had zijn of haar eigen huishouden. In Leopoldina's geval speelden twee vrouwen een belangrijke rol in haar kleine wereld. De ene was Maria Ulrica, de belangrijkste hofdame, die verantwoordelijk was voor het onderwijzen van goede manieren, etiquette en ceremoniële gebruiken, en die haar studies begeleidde. De andere was Francisca Annony, die zorgde voor de kleding, hygiëne en persoonlijke verzorging van de aartshertogin. Francisca was al sinds haar jeugd haar dienstmeid en koesterde grote genegenheid voor haar.

Deze twee vrouwen bleven bij Leopoldina Gedurende haar hele jeugd en een deel van haar jeugd. Zoals gebruikelijk onder de adel en de hogere klassen, werd de aartshertogin nooit alleen gelaten, zelfs niet tijdens haar slaap. Dit lijkt ons vandaag de dag misschien vreemd, maar het moderne concept van privacy was toen niet van toepassing, zeker niet op iemand van Leopoldina's adellijke status, die altijd vergezeld werd. Zelfs tijdens haar aangewezen brieven was ze nooit alleen.

Leopoldina's stiefmoeder was zeer begaan met de opvoeding van de kinderen die ze uit het vorige huwelijk van haar man had geërfd. Ze hield persoonlijk toezicht op hun studies en legde zelfs straffen op als ze weigerden te studeren. Leopoldina ontving catechismus en deed haar eerste communie. In 1810 trad ze toe tot de Orde van het Sterrekruis, een uitsluitend vrouwelijke en aristocratische orde. De leden waren toegewijd aan gebed, verering van het Heilig Kruis, een deugdzaam leven, geestelijke bijstand en liefdadigheid.

Europa was destijds verre van vredig. Leopoldina's zus was getrouwd met Napoleon – en ik denk dat ik niet veel over hem hoef uit te weiden, aangezien hij een bekende historische figuur is die het continent in oorlogen stortte. Hierdoor ging de gezondheid van Leopoldina's stiefmoeder achteruit, nog verergerd door de vlucht uit Wenen en het feit dat haar stiefdochter getrouwd was met de man die chaos in de wereld bracht. Daarom besloot ze Leopoldina mee te nemen naar het kuuroord Karlsbad, in de hoop dat de frisse lucht haar gezondheid zou herstellen.

In Karlsbad genoot Leopoldina niet alleen van haar vakantie. Ze nam deel aan studiereizen en bezocht plantages, veehouderijen, fabrieken, kassen, gieterijen en mijnen, maar ook musea, botanische tuinen en rariteitenkabinetten. Na elk bezoek schreef ze gedetailleerde verslagen. Zo verbreedde ze haar wereld – niet alleen wetenschappelijk, maar ook door de interactie met diverse mensen: arbeiders, boeren en zelfs mijnwerkers.

Het verblijf in Karlsbad diende tevens als een soort strategische terugtrekking uit het Weense hof, terwijl er politieke onderhandelingen gaande waren. Oostenrijkse diplomaten, zoals de invloedrijke prins Metternich, werkten achter de schermen aan het regelen van Leopoldina's verloving met Dom Pedro. De reis naar Karlsbad hield Leopoldina tijdelijk op afstand van de nieuwsgierige blikken en het gefluister uit Wenen – maar bracht haar ook dichter bij de realiteit van internationale huwelijksonderhandelingen. Dit proces kostte tijd, en tijdens de onderhandelingen vroeg Leopoldina's vader zelfs om Portugese boeken, zodat zijn dochter de taal kon leren die ze in de komende jaren nodig zou hebben.

De kindertijd en jeugd van Maria Leopoldina getuigen niet alleen van een voorbeeldige opvoeding, maar ook van de vorming van een vrouw die klaar was voor een grootse toekomst. Haar studie, discipline en gevoeligheid zouden een aartshertogin vormen die al snel de oceaan zou oversteken om haar naam in de geschiedenis van Brazilië te schrijven.

Referentie: REZZUTTI, Paulo. D. Leopoldina: een niet-contada-geschiedenis: Een verhaal dat een onafhankelijkheid van Brazilië heeft opgeleverd. Brazilië: Leya, 2022.

Matheus Araújo

Matheus Araújo is de bedenker en redacteur van Brazilian History. Geboren in Rio de Janeiro en afgestudeerd in Reclame en Propaganda, bracht zijn passie voor geschiedenis hem ertoe om zich in te schrijven aan de Federale Universiteit van de Staat Rio de Janeiro, waar hij momenteel een lerarenopleiding Geschiedenis volgt.